NuSTAR telescope captures Sun's hidden lights: It may help solve one of Sun's greatest mysteries

Thanks to photos taken by NASA's Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR), it has become possible to see some of the hidden light emitted by the Sun that the human eye cannot see even on the sunniest days. This could help scientists solve one of the greatest mysteries of the Sun.

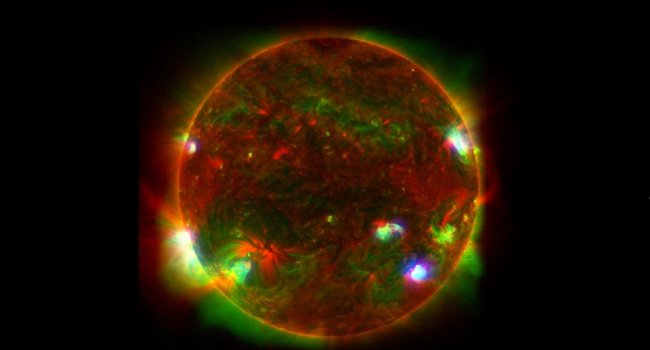

A new NuSTAR image shows some of this hidden light, including high-energy X-rays emitted by the hottest material in the Sun's atmosphere, NASA said.

Although NuSTAR typically studies objects outside our solar system, such as massive black holes and collapsed stars, it is now also helping astronomers learn more about the Sun.

In the left composite image above, the NuSTAR data is shown in blue and combined with the X-Ray Telescope (XRT) image from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency's Hinode mission, shown in green, and then and the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly on NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), represented as red.

NuSTAR's relatively small field of view means it can't see the entire Sun from its position on Earth's orbit, so the image of the Sun actually consists of 25 images taken in June 2022.

The high-energy X-rays observed by NuSTAR appear only in a few places in the Sun's atmosphere. In contrast, the Hinode XRT picks up low-energy X-rays, and the NASA Solar Dynamics Observatory image shows ultraviolet light whose wavelength is emitted by the entire surface of the Sun.

Solving one of the Sun's biggest mysteries

An image taken by NuSTAR in 2012 could help scientists unravel one of the Sun's biggest mysteries. Why does the Sun's outer atmosphere (called the solar corona) reach temperatures of more than a million degrees, which is at least 100 times higher than the Sun's surface? This question has puzzled scientists because the Sun's heat emanates from its core and spreads outward, and it would make sense if the Sun's surface were hotter than the outer atmosphere.

The source of heat in the solar corona can be small eruptions in the Sun's atmosphere, called nanoflares. Flares are large bursts of heat, light, and particles visible to a wide spectrum of solar observatories. Nanoflares are much smaller events, but both types produce material that is even hotter than the average coronal temperature. Ordinary flares do not occur often enough to keep the corona at the high temperatures recorded by scientists, but nanoflares can occur much more frequently, perhaps often enough to collectively heat the sun's corona.

Although individual nanoflashes are too faint to be observed in bright sunlight, NuSTAR can pick up light from the high-temperature material, which is thought to form when a large number of nanoflarhes occur close together. This ability allows physicists to study how often nanoflares occur and how they release energy.

- Related News

- Once in a lifetime phenomenon: This year we will observe a star explosion that occurred 3,000 years ago

- "AMADEE-24" Mars Analog Research Mission in Armash came to an end

- NASA creates new generation solar sail: What is it for?

- Flying object resembling surfboard was detected in Moon’s orbit: What is it in fact?

- Total solar eclipse on April 8, 2024: The most impressive photos

- Total eclipse of Sun will take place today: From which parts of the country will it be seen?

- Most read

month

week

day

- iPhone users are advised to disable iMessage: What risks are hidden in it? 1501

- Problems with Android 15: NFC contactless payments no longer work on smartphones with updated operating systems 1201

- Pavel Durov gives interview to Tucker Carlson: From 3-hour interview, less than hour appears in final version 1140

- AMD Ryzen 7 processor, 24 GB of RAM and only $550: Mechrevo presents inexpensive and powerful laptop (photo) 851

- The 5 most controversial buildings ever built: Bold design or complete failure? (photo) 806

- Black Shark smart ring from Xiaomi to have interesting characteristics and phenomenal autonomy: 180 days of operation without recharging (photo) 804

- Armenia takes 89th place in terms of mobile Internet speed, but leads region in terms of fixed line speed 729

- 3 best smartphones under $160 681

- Telegram receives major update and sticker editor 656

- No internet access required? How AI will work in iPhone 594

- Archive